Scriptures from the Fourth Week of Advent

2 Samuel 7:1-11, 16 (NRSV)

7:1 Now when the king (David) was settled in his house, and the LORD had given him rest from all his enemies around him, 2 the king said to the prophet Nathan, "See now, I am living in a house of cedar, but the ark of God stays in a tent." 3 Nathan said to the king, "Go, do all that you have in mind; for the LORD is with you."

4 But that same night the word of the LORD came to Nathan: 5 Go and tell my servant David: Thus says the LORD: Are you the one to build me a house to live in? 6 I have not lived in a house since the day I brought up the people of Israel from Egypt to this day, but I have been moving about in a tent and a tabernacle. 7 Wherever I have moved about among all the people of Israel, did I ever speak a word with any of the tribal leaders of Israel, whom I commanded to shepherd my people Israel, saying, "Why have you not built me a house of cedar?"

8 Now therefore thus you shall say to my servant David: Thus says the LORD of hosts: I took you from the pasture, from following the sheep to be prince over my people Israel; 9 and I have been with you wherever you went, and have cut off all your enemies from before you; and I will make for you a great name, like the name of the great ones of the earth.

10 And I will appoint a place for my people Israel and will plant them, so that they may live in their own place, and be disturbed no more; and evildoers shall afflict them no more, as formerly, 11 from the time that I appointed judges over my people Israel; and I will give you rest from all your enemies. Moreover the LORD declares to you that the LORD will make you a house… 16 Your house and your kingdom shall be made sure forever before me; your throne shall be established forever.

Luke 1:26-38 (NRSV)

1:26 In the sixth month the angel Gabriel was sent by God to a town in Galilee called Nazareth, 27 to a virgin engaged to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David. The virgin's name was Mary.

28 And he came to her and said, "Greetings, favored one! The Lord is with you."

29 But she was much perplexed by his words and pondered what sort of greeting this might be.

30 The angel said to her, "Do not be afraid, Mary, for you have found favor with God. 31 And now, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you will name him Jesus. 32 He will be great, and will be called the Son of the Most High, and the Lord God will give to him the throne of his ancestor David. 33 He will reign over the house of Jacob forever, and of his kingdom there will be no end."

34 Mary said to the angel, "How can this be, since I am a virgin?"

35 The angel said to her, "The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be holy; he will be called Son of God.

36 And now, your relative Elizabeth in her old age has also conceived a son; and this is the sixth month for her who was said to be barren. 37 For nothing will be impossible with God."

38 Then Mary said, "Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word." Then the angel departed from her.

This is the Word of God, for the community of God. Thanks be to God.

_________________________________

Homily for a CreatureKind Advent Service

By Ashley Lewis

An angel shows up at the house of a young woman and says she will be given a son, who will be called “Son of the Most High.” This son will be given the throne of David and will reign over the house of Jacob with an everlasting kingdom.

What a terrifying, puzzling, mysterious, wonderful, beautiful promise?

A throne. A kingdom. An everlasting reign. For nothing will be impossible with God.

Hearing these words from God’s messenger, Mary must have considered the lineage into which she was now birthing her son. The very lineage that we read about in 2 Samuel. David, the favored son of God, who was brought up out of the pasture to a palace, to become king of Israel. Whose son built the temple, the house of God. The promise God made to David, and to Jacob before him, would be fulfilled in Jesus the son of Mary.

So, perhaps she thought her royal treatment would begin promptly! Maybe she envisioned the kingdoms of the world crumbling at her feet as her son grew from boy to man. Maybe she thought that upon Jesus’s birth, the house of God would begin to overshadow the palaces of Rome and that she would come to live as a queen in a new dynasty. She might have imagined that under the rule of her son, fairness and equity and justice would prevail, and that despair, poverty, and idolatry would no longer have a place in the world. The corrupt empires that exploit humans, animals, and the earth would be abolished. She probably thought Jesus would deliver them from homelessness and wandering into an everlasting home with God, where all Creation would be at peace.

Is that the vision that made Mary say yes? If she knew what Jesus’s life would really be like, would she have said, “Let it be with me, according to your word?”

Because Jesus never occupied an earthly throne. His kingdom did not appear to break the hold Rome had over the world. In fact, he didn’t ever even stay in one place, much less have a palace. He wandered. He was a traveler. As a man, he had no place to lay his head and was not welcomed even in his hometown. As a baby, he was born in someone else’s house and given a feedbox for a bed.

The house where Jesus was born was most likely a distant relative of Joseph. And contrary to popular thought, Jesus and his parents were not made to stay in a stable, outside. Stables didn’t exist in first century Palestine. Instead, the common room of the house, on the first level, was where humans and animals lived together. It would have been preferable and much more appropriate for guests like Mary and Joseph to be given the guest room, upstairs, where they could have privacy. But all the guest rooms in town were occupied, so this family-member who welcomed Mary and Joseph gave them what they had:

A corner of the common room.

Warmth.

Bread.

Prayers.

A place to sleep.

And when Jesus made his appearance into the world as a human child, even the animals gave up what they had for him. The manger, where they were used to seeing hay and feed, was now occupied by a baby.

Perhaps the sheep and the goats were perplexed by Jesus’s presence in their trough. Surely, they’d be wondering where their food was, staring at him, smelling him and the space all around him, pondering why he’s occupying the place where their dinner should be. Like our pets when we move their food bowl.

I’d like to think Jesus’s presence pacified them in their confusion. This child would later offer his body up for the sin of the world, breaking bread, pouring wine, shedding his own blood, and indoctrinating creation into a new covenant with God.

But, long before Jesus sat at the table and broke bread with his disciples, he laid among the animals—in place of their food.

Watching over Jesus on the night of his birth, Mary must have wondered when all these grand promises were supposed to start coming true, as the angel said? How would such a house be established? When would Jesus take the throne? How would God get them from here to there? What would it be like to be given a place all their own, planted in the presence of the Lord, and disturbed no more by the corrupt forces of the world? When would they be delivered from pasture into paradise?

Let it be, Lord, according to your word!

When we envision God's kingdom coming to life in this world, we often imagine it taking place in the grandest way. We suppose the so-called powers and principalities will crack and crumble, as a new, just ruler takes the throne.

But our God is prone to wander, from place to place, in a tent and a tabernacle, not afraid to seek shelter in someone else’s house or among the animals, taking up residence in the unlikeliest of places… in a crowded room, sharing bread and warmth and prayers, reclining at the table, or in the manger, where human and non-human alike can bear witness to this new sort-of kin-dom.

The thing about Emmanuel—God with us—is that if God’s going to be with us, God’s gotta be able to go where we go.

Emmanuel—God with us—is at home in our hearts and at our tables. In our mess, and in the messes we make. God can’t be locked away in a palace, or a white house, or on a throne. God of Creation is at home in creation, with creation.

In the skies and in the oceans. In the cities and in the countryside. In the stars above our heads and in the earth beneath our feet.

In a manger. In a crowded family room. In the company of humans and non-humans. In the wild places and in our domestic comforts, whether welcomed or estranged.

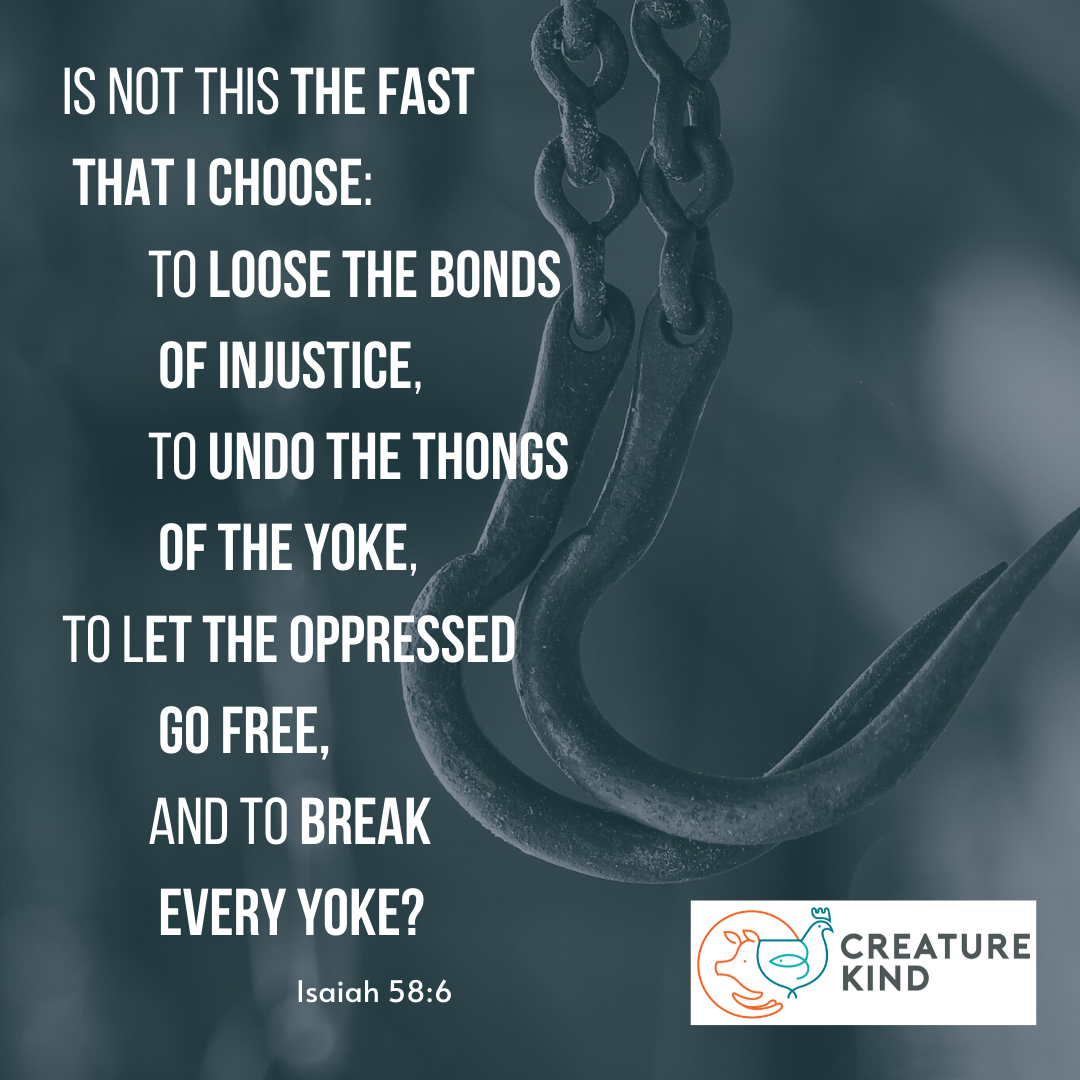

God takes up residence where hope is needed the most. With the homeless. With the oppressed. With the depressed.

In the slaughterhouses and on the killing room floor. In the prisons and at the borders. In the fields, and in the factories.

What a terrifying, puzzling, mysterious, wonderful, beautiful promise.

A manger. A savior. An everlasting reign. For nothing will be impossible with God.

Let it be with me according to your word.