Written by Liesl Stewart

I remember eating my last hamburger when I was fourteen years old. As I chewed, I had a firm and clear knowing: this is the last hamburger I will ever eat. That was forty years ago, and I’ve never eaten one since. I started to move away from consuming meat because somehow I had begun losing the taste for its meatiness, and I couldn’t disassociate the food I was putting in my mouth from the farmed animals from which I knew it came.

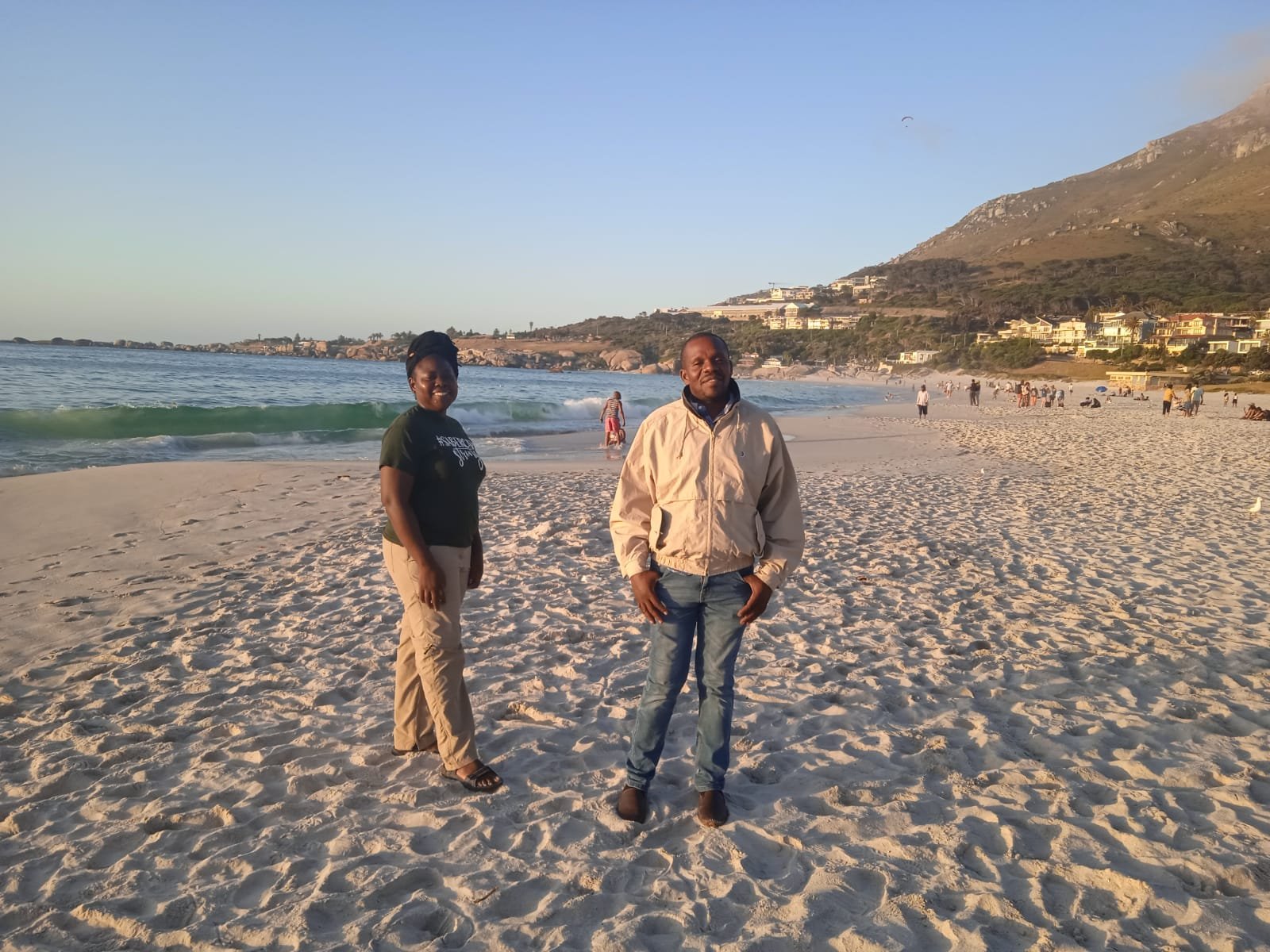

More precisely, I’ve long been a pescetarian–a vegetarian who also eats seafood. (When I first heard the term from friends newly describing themselves as pescetarians, I thought they’d joined some kind of strange eco-cult!) Now forty years on, I still live as a pescetarian, set on a trajectory that arcs more in the direction of plant-based eating with every year I live. I eat much less fish and dairy now than I used to. My relationship with the consumption of animal-based foods is not fixed; I’m constantly renegotiating the terms of my food choices based on what I have learned about the food system, the foods I have access to, and my developing values. I’ve seen similar shifts in my family members’ diets.

Earlier in life, I didn’t have a theological basis for my choice to stop eating meat. I began forming this theology sometime in my thirties when I stumbled across Gen 9:3-4. When making a covenant with Noah after the flood, God seems to give humankind permission to eat animals.

Every moving thing that lives shall be food for you, and just as I gave you the green plants, I give you everything. Only, you shall not eat flesh with its life, that is, its blood. (NSRV-UE)

What?! Were people not supposed to eat animals before? I went back to the original Creation accounts at the beginning of Genesis. Yes, there it’s written:

Then God said, “I give you every seed-bearing plant on the face of the whole earth and every tree that has fruit with seed in it. They will be yours for food. And to all the beasts of the earth and all the birds in the sky and all the creatures that move along the ground—everything that has the breath of life in it—I give every green plant for food.” And it was so. God saw all that he had made, and it was very good. (Genesis 1: 29-31b NRSV-UE)

God affirms this again, when, as Eve and Adam were banished from Eden, God told Adam to “eat the plants of the field” (Gen 3:18). It wasn’t until Noah’s storyline, when God made a new covenant between God and humankind, that animal creatures were permitted to be killed and eaten. Judith Barad has pointed out that, in Genesis 3, the original covenant God made was with both humans and non-human animals, and that it is written six times for emphasis. “There is a kinship between humans and other sentient beings, a kinship which is made explicit in the covenant.”3

I don’t know why God offered this permission, nor is it my intention to interpret these verses and declare God’s edicts in this blog. There are different approaches to reading the first chapters of Genesis. For me, I believe that the genre is story–specifically, Creation and covenantal stories–which are often told using poetry. Rev. Dr. Christopher Carter suggests the Creation accounts in Genesis use liturgical poetry, which “invites us to see Creation through a divine perception that encourages a healthy imagination to think and feel in ways that promote relationality and interdependence.”4

My theological formation regarding the kinship of all creatures has continued as I have engaged more and more with nonhuman animals: living with dogs in our family; caring for chickens in our garden; rescuing abandoned fledgling robin-chats and injured pigeons and juvenile hadada ibises; welcoming local birds to our bird feeder; and even marveling at the diversity of insect life I encountered in my garden and my home. I have seen animals emote, communicate, show unique personalities, and bond with human and nonhuman others. I’ve admired their social intelligence. I have cried when they’ve died. (My daughter’s beloved rat, Gandalf, lived the last week of his life sick on my chest or my daughter’s neck. We sobbed our hearts out together when he died, and we still talk about how much we adored that guy.) I’ve even spoken to insects scurrying away from me: “I see your strong instinct for survival, and I respect that life in you!” (Yes, that’s me talking to cockroaches and spiders!)

My theology has also continued to form as I have interacted–through a food-buying collective–with the people who make the food I eat. Through God’s provision, the source of all the food we eat is Creation. My love for Creation has grown as I’ve interacted with producers, learning from them about the complexities of growing and producing food with care given to the land and animals, human and nonhuman. Ecosystems held in balance become fragile when we humans treat Creation as if it’s something to be exploited.

When we examine the treatment of animals used for food in today’s context, how are our fellow creatures faring?

Today, billions of animals are raised and killed in industrialized factory farms for human food. These farmed animals endure miserable lives and cruel deaths. They are crushed under the oppressive weight of industrialized food production. Any values or intentions God has communicated in the Creation accounts or in the covenant with Noah surely do not bless this kind of exploitation and suffering.

The theologies from which we live often begin with questions born out of realities that disturb us. In being disturbed we might be challenged to change the behaviors that are contributing further harm. If we understand that most or all of the meat, dairy, and eggs available at grocery stores come from animals raised in factory farms, will our food choices change as a result? Here are some questions I’ve found helpful to examine how theology might impact our decisions about food choices:

• How does your own understanding of God and Creation guide you in deciding what to eat?

• How has your theology been formed, and how are you able to support your own continued formation?7

• In your context, are there ways that you would want to change your eating habits?

• If change seems daunting, are there small changes you could make that would help your habits better align with your beliefs?

• Are there people you trust, or people whose hearts are similarly moved by these issues, with whom you could explore this topic?

• What small or big practical steps could be taken to reflect God’s caring for Creation?

At CreatureKind we’d love to help you think through ways to engage further. Our DefaultVeg program will help you begin to make some changes that are good and right for your community’s context. Please reach out to us for additional conversation or support.

2. Judith Barad, “What about the Covenant with Noah?” in A Faith Embracing All Creatures: Commonly Asked Questions about Christian Care for Animals, eds. Tripp York and Andy Alexis-Baker (Eugene: Cascade Books, 2012), 14↩

3. Judith Barad, “What about the Covenant with Noah?” 19.↩

4. Christopher Carter, The Spirit of Soul Food: Race, Faith, and Food Justice (University of Illinois Press, Champaign, 2021), p. 89 of Chapter 3, Rakuten Kobo.↩

5. One of the best ways we can help farmed animals is by reducing our consumption of animal products, especially those reared within factory farming systems. There are different ways to do this. We can adopt a plant-based diet altogether, as advocated by the author of this blog; or we can reduce our consumption of animal products, and source what we do consume from the highest welfare providers. ↩

6. Christopher Carter, in his book, The Spirit of Soul Food: Race, Faith, and Food Justice, discusses in detail how problematic this view is in Chapter 3, the section: “Race, Religion, and the Creation of “The Animal”, p. 55-75, Rakuten Kobo.↩

7. If you would like to learn more about a theology of animal treatment, our CreatureKind website has blogs to help you, as well as other resources. https://www.becreaturekind.org/↩