by Jeania Ree V. Moore

When recounting his beginnings as a civil rights activist, Congressman John Lewis often started with Big Belle and Li’l Pullet, two valued members of his childhood congregation. For this flock, Lewis was not a follower, but a leader. Lewis was put in charge of the chickens on his Alabama family farm as a young boy. Being a child who loved church and loved his chickens, Lewis ministered to the sixty Rhode Island Reds, Dominiques, bantams, and other birds under his care while daily feeding them and tending their nests. He preached, taught, exhorted, prayed over, and even baptized them so regularly that his siblings began calling him “Preacher.”

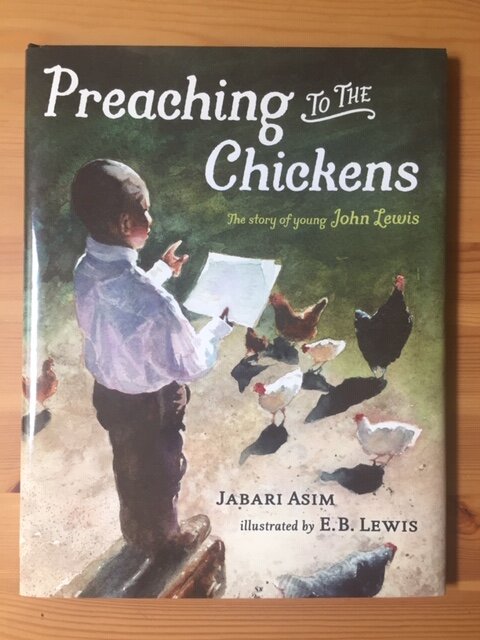

Lewis’s humorous and earnest origin story is captured in the children’s book Preaching to the Chickens: The Story of Young John Lewis (2016), written by Jabari Ansim and illustrated by E.B. Lewis. Beautiful illustrations and cheerful text depict John Lewis and the chickens apprehending the gospel through their life together. Big Belle, a hen whom Lewis saves after she falls down a well, is proof of God’s presence and everyday miracles. Li’l Pullet, a chick who is revived after an apparent drowning during Lewis’ baptismal ministrations, testifies to God’s healing power. Lewis’s intervention in the pending sale of the birds teaches him justice and faith in standing up for others.

As we reflect on Congressman Lewis in the wake of his death and consider what he taught us through the life that he lived, it is worth sitting with this story. Preaching to the Chickens situates Lewis in the company of Saint Francis of Assisi, patron saint of animals, as well as the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., a leader in the Civil Rights Movement. Drawn from recollections in Lewis's memoir Walking with the Wind, this book locates the roots of a central freedom fighter of our age in a peace ethic learned through early encounters with fellow creatures of God. It reveals deep currents connecting the traditions of love, justice, and care for human and nonhuman animals, focusing here on farmed animals. It shows how these traditions form a larger theological vision within the Christian faith. In this vision, human and nonhuman creatures alike are recipients of the Good News, God’s concern for each particular creature provides a model for human concern, and delight in the goodness of God and creation grounds daily living.

This portrayal of John Lewis, preaching to the chickens, is a contemporary image of the Peaceable Kingdom—an icon offering revelation for us today.

This portrayal of John Lewis, preaching to the chickens, is a contemporary image of the Peaceable Kingdom—an icon offering revelation for us today. Young John Lewis participated in the Peaceable Kingdom as a reality. His witness suggests that, rather than considering peace among humans, animals, and creation as a dream for some far-off time after our violent present, we should embrace it as a reality to come, with consequences for living in the here-and-now.

John Lewis took the Peaceable Kingdom as a starting point for his journey in moral courage. We should follow his example.

Jeania Ree V. Moore is a United Methodist deacon who works in justice, theological education, and writes "Under the Sun," a column for Sojourners magazine. She serves on the Board of Directors for CreatureKind.